- Home

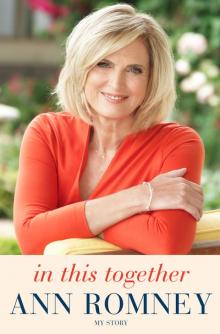

- Ann Romney

In This Together Page 3

In This Together Read online

Page 3

“We believe in God, the Eternal Father,” he said, “and in His Son, Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Ghost.” In very simple terms he explained that his faith gave his life purpose and meaning.

I was struck by that. Obviously I had been searching for something. I was overwhelmed by the simplicity of what he was saying, and it all started to make sense to me. Windows opened and sunshine came in. I felt like I’d found the missing piece of my life. Eventually George Romney baptized me, and since then my religious beliefs have remained very important to me.

So, when I was given this diagnosis, I asked the same question that has been asked at challenging times forever: Why me?

There was no answer to that question. My father eventually concluded that God gave each of us the right to make our own choices, and that the good or the evil things that happened were the result of those decisions. But he also believed that it was up to us to chart our own fates and that little could be accomplished by sitting and waiting. God made the world, but it was up to each of us to make our own way through life. God didn’t give me this disease. It was up to me to deal with it.

The day I was diagnosed, Mitt and I went home from the hospital with a brochure about MS that answered all our immediate questions, as if we’d bought a washing machine and had been given a pamphlet outlining its extended warranty. To me, it seemed like a map to nowhere.

As I began adjusting to my new reality, my physical condition got worse every single day. It felt like there was a wildfire raging through me. I would wake up in the morning wondering what part of my body would be attacked that day. The numbness in my leg had started at a spot near my knee; it had now travelled all the way down to my toes and up to my torso. I was starting to have incontinence issues. I tried desperately to fight back as much as I was able. Keep moving, I told myself, maybe if you keep moving it won’t catch up with you. I’ve always loved swimming, so I went to the pool to try to swim a few laps. I struggled through those few short laps and then went to the changing room. I’d always had such beautiful hair, and taken so much pride in always looking well groomed, but in that changing room, when I tried to blow-dry my hair, I couldn’t do it. It was too hard for me. I couldn’t hold up the dryer for more than a few seconds. It was a terrible dilemma. The swimming was supposed to have made me feel better, but if my hair looked awful, I would feel lousy about myself. So I stopped swimming. My hair was part of my identity; I couldn’t give up my appearance. I was trying desperately to hold on to every little bit of normal life as long as I could.

As much as possible, I tried to avoid thinking about the future, but it was unavoidable. I was starting to accept the possibility that I would very quickly lose the use of my leg, and perhaps even need a wheelchair. Mitt and I were in the midst of building our dream house in Park City, and we went back to the plans to add the elevator I would now need to get from floor to floor. But an elevator wasn’t nearly enough: that numbness eventually was going to affect my organs; this disease was going to kill me.

I was neither physically nor emotionally prepared to deal with my symptoms. I tried to learn as much as possible about my enemy. I guess I was looking for the loophole in my diagnosis. I was confident that somewhere in those neatly printed facts in that bright brochure there just had to be some hope for me. It didn’t seem possible that after all the advances science had made in fighting once-terrifying diseases that there was no treatment for MS, that the best thing that a fine doctor could offer was to go home until it got worse.

Multiple sclerosis, I learned—and eventually I would learn far more than I’d ever wanted to know—is an autoimmune disease, meaning that my own immune system cells were attacking my body. No one understands why this happens, although there is some speculation that it begins with an infection from a virus that has a structure similar to the cells normally found in the brain, so the immune system attacks both that virus and the healthy areas of the brain. Specifically, it attacks the myelin sheath, the protective insulation that surrounds nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord and allows the flow of electricity from the nervous system directly to the muscles. By essentially eating away the myelin sheath, MS prevents that flow. Basically, it keeps the brain from telling your muscles what to do. It’s like covering the speaker on your phone and trying to talk—some of the information will get through, but not very clearly. Initially the myelin sheath can heal itself, but eventually it loses the ability to make the necessary repairs.

The more I learned about it, the more confusing, and scary, it became. The ability of steroids, at least temporarily, to alleviate the severity of an attack was discovered in the 1960s, although the disease was known for hundreds of years before that. There are written reports of people suffering from similar symptoms in the Middle Ages, although MS wasn’t identified as a disease until 1868. That year, Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot, a professor at the University of Paris, who is remembered as “the father of neurology,” dissected the brain of a former patient and discovered the characteristic hard nodules, the scars, or plaque, found in MS patients. He therefore named the disease sclérose en plaques. Charcot was frustrated that it resisted all the standard medical treatments of that time, including injections of a minute amount of the poison strychnine and even of gold and silver.

It wasn’t until 1916 that greatly improved microscopes allowed Scottish researcher James Dawson to describe the effects of the disease in the brain, but the fact that it was an autoimmune disease wasn’t known until the 1960s. The development of magnetic resonance imaging in the 1980s allowed scientists for the first time to track the progression of the disease and the effects—or, more often, the lack of effects—of potential treatments.

What has always made MS so difficult to diagnose or treat is the fact that the symptoms and progression of the disease are different in every case. Not only is it unique in each patient, but it can even change over time in an individual. That said, we know today that there are two basic categories of MS. The first is progressive MS, where the symptoms proceed without interruption toward greater and greater disability. The other is relapsing-remitting MS, where an attack of symptoms is followed by a remission. The remission does not typically return the person to full recovery, however. Instead, it leaves him or her diminished but temporarily stable. In some cases, relapsing-remitting MS becomes progressive. The great majority of MS sufferers, me included, have the relapsing-remitting form of the disease. A relapsing attack may affect one part of the body, such as eyesight, and then go into remission. Then weeks, months, or years later, it may attack a different part of the body, such as the legs.

Plaque appears in the brain and then disappears. Symptoms will get worse, and then the patient will go into remission. What makes MS so different from other neurologic diseases is that most of them are localized to a single place in the nervous system, while the symptoms of MS appear in many places in the body. And there are a wide range of symptoms, including tremors, an inability to grasp things, tingling and numbness, loss of the use of some or all your limbs, double vision, and even temporary blindness. Rarely, it also can cause personality change: There have been cases in which people become belligerent, hypersexual, or completely uncontrollable. Attacks can come without any warning and can be severe or mild; they can last a few days or a few weeks, or linger for considerably longer; they can relapse or be progressive.

It’s sort of the whack-a-mole of diseases: when it is knocked down in one place, it appears in another. It may stay dormant for a while, but then reappear stronger than before. Whatever the course of the disease, however, it is devastating.

When I was diagnosed, I was one of more than two and a half million to suffer from it. It remains the leading cause of paralysis in younger people. It tends to appear more in women than men, and more often in the northern, cooler latitudes than warmer regions. For hundreds of years, scientists have been searching for a vaccine to prevent MS and the other neurologic diseases, or find effective treatments for them. Every time there w

as a new development or breakthrough in the treatment of a disease, someone would try to adapt it to MS. Jonas Salk, after developing the polio vaccine, turned his attention to MS, but without any success. In a 1978 trial, most of the patients who received his vaccine showed little or no improvement, and in fact, some got worse. Some experiments done on MS over the years have had at least a temporary effect in controlling some symptoms in some patients. Steroids and certain chemotherapy drugs had a positive effect.

As I read this information, I paused and took a deep breath. This was the first glimmer of hope I’d had: a lot of people were studying this disease; there were success stories. But there was no way of predicting what worked for each patient, for how long, or why.

One of the leaders in the research and treatment of MS, a doctor name Howard Weiner, was working at the MS Center he founded at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Two months after my initial diagnosis, a good friend of ours, Dr. Gordon Williams, a noted endocrinologist also at the Brigham, arranged an appointment for me. In addition to running the MS Center, Dr. Weiner and his close friend Dr. Dennis Selkoe were codirectors of the Center for Neurologic Diseases, which was founded in 1985. (It was called that, I later learned, because the two men decided that using the word neurologic rather than the more common neurological would catch people’s attention.) Like Weiner, Dr. Selkoe, one of the world’s leading experts on Alzheimer’s disease, had his own center: the Alzheimer’s Disease Center. Dr. Weiner and Dr. Selkoe treated patients in their respective centers, but joined to create the neurologic center as an experimental research laboratory. If anyone could do something to help, Gordon Williams told us, it was Dr. Weiner.

The day I walked into his office, I could not possibly have imagined how much both our lives were going to be changed. Dr. Weiner was warm and welcoming, and immediately made me feel that we were in this fight together. As I was to discover, he had spent his entire career battling this enemy and had begun very slowly making progress. Treating MS was not simply his profession; it was his passion.

Weiner was born to be a doctor. His Austrian-born parents had fled Vienna with their families in 1939 and married after settling in Denver, Colorado. His maternal grandfather, Samuel Wasserstrom, had gotten a special visa to leave Austria and was on the passenger ship with his bags when he was taken off. His bags arrived in Denver; he died in Auschwitz. But he had written a letter to his daughter asking her to promise that if she had a son, he could become a doctor. It was an odd request; Wasserstrom was himself a furrier. No one understood it, and in most cases it would have been an impossible promise to keep. But as Howard Weiner once told me, “When I was growing up, I just heard from my mother all the time, ‘You’re going to be a doctor.’ As I got older, when I would walk by a hospital, I actually felt that I needed to be there.”

At Dartmouth he was a philosophy major, so when he entered medical school, he decided the brain was our most interesting organ to study and became a neurologist. As a first-year neurology resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, he remembered, “I took care of a man about my age that had MS. In many ways I identified with him: he had two sons, I had two sons. He’d had an MS attack and recovered from it. There are many diseases that people don’t recover from; they just get progressively worse. Alzheimer’s disease doesn’t stop. Lou Gehrig’s disease doesn’t go away. But the fact that he had recovered was fascinating for me, because it suggested there are natural mechanisms that can change the course of this disease. So I decided at that time that I wanted to study the disease.”

Dr. Weiner experimented with various treatments throughout his career. In the early 1970s, for example, researchers wondered if the disease could be stopped by eliminating from the bloodstream the antibodies that attacked the myelin sheath. In this plasma exchange, which in some ways is similar to a stem cell transplant, plasma is taken from a patient and the toxic factors are removed—in this case, the antibodies would be removed—and then the blood is reinfused. Initially some of Dr. Weiner’s patients were afraid to go through this unproven process, so Dr. Weiner went through the plasma exchange treatment himself, to prove to his patients that it was safe. The needle hurt, he remembers, but the process itself caused no problems. Still, while his theory made sense, the results were disappointing.

Yet, as I was about to find out, Dr. Weiner had made substantial progress since then.

In mid-December 1997, Mitt and I were sitting in his office at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, desperate for even the slightest suggestion that there was something we could do to help control my disease. Dr. Weiner looked at my MRIs and conducted most of the same tests my first doctor had done. Once again, I failed every test. “Looks like sclerosis has already developed on your spine,” he said, confirming the earlier diagnosis. I had MS. Then I showed him the extent of the numbness in my body during that initial visit and how much it had progressed in the ensuing two months. He listened silently as we told him what my first doctor had said, but I noticed that when I told him we had been advised to go home until my symptoms got worse, he shook his head in disdain. I took that as a positive sign.

We asked him many of the same questions we had asked the first doctor. His answers were pretty much the same, but the cautiously optimistic tone in his voice somehow made them less frightening.

The one thing he could not do was predict the path of my disease.

“What should I expect?” I asked.

“The unexpected,” he said, although those weren’t his precise words. The insidious thing about MS was its unpredictability, he explained. This is what made it so different from other neurologic diseases. And while some progress had been made in understanding the cause and course of MS, there still was no way of knowing how it would affect a given patient. He told us about several of his patients who, with just a little assistance, had been able to lead almost normal lives.

Finally, he told us that while treatment remained an inexact science, waiting was not one of the options. “What they’re telling you is crazy,” he said. “We’ve got to knock this thing down. I can’t tell you we can cure it, but we can treat it.” He told us that I had relapsing-remitting MS, although it was progressing very rapidly. My experience with the disease was not unusual. Once the relapsing type strikes, it can move through your body very rapidly and result in severe disability. The most important thing to do was blunt that initial attack to prevent the loss of motor function. If we didn’t stop it very quickly, he continued, it could lead to significant and permanent disability. Dr. Weiner proceeded to tell us about several different strategies he had used, sometimes very successfully, to help other people with this form of MS. Then he stood and offered me his hand. “We’re going to attack it and we’re going to start right now,” he said. “Come with me.”

I was stunned. I almost burst into tears. There was no equivocation in his voice: Come with me. Those words offered the first real hope that there was some way of fighting back.

Dr. Weiner literally led me by the hand down the hall into what is known as the infusion room. There were several other men and women in the room, sitting quietly with needles in their arms as some liquid dripped slowly into their bodies. While the fact that we were taking the offense gave me comfort, as I looked around the room I became terrified that I was looking at my own future. Most of these people were in wheelchairs, several of them with bladder bags hanging from the sides.

I sat down in an infusion chair, and a nurse-practitioner came over and sat next to me. Apparently she had seen the fear in my eyes. She patted me reassuringly on my arm and whispered, “Don’t be too concerned about all these other people. Everybody’s response to treatment is different. This doesn’t mean you’re going to have to be this way.” Be positive, she continued. Be cheerful; you’re going to be okay. I heard every word, and I tried to believe her. And a little of me did believe it might not be as terrible as I thought. But as I looked around I saw pretty graphic evidence of where this disease can take you.

Dr. Weiner explained his strategy to me: Hit it early, hit it hard. Don’t let it take root. He was blasting my body with a steroid, cortisone, one of the drugs most commonly used to fight MS. For some people it worked amazingly well, for others it had no effect. Doctors did not yet understand the reasons for this. When I asked him why my first doctor hadn’t tried this, he didn’t have an answer. MS is a disease for which there is no standard treatment protocol, he explained. In many ways, treating it is an art. He suggested that the difference in approaches might be due to the fact that in the past many of the neurologic diseases couldn’t be treated, so the profession attracted people who liked to diagnose it, think about it, research it, and do anatomy, but who did not have the same treatment culture as other medical disciplines.

That just wasn’t him, he told me, and then he quoted King Lear’s wise advice, “Nothing will come of nothing.”

In the early 1980s, Weiner had performed a series of experiments treating MS patients with chemotherapy and had discovered that “strong modulations in the immune system could make a big difference in the outcome.” Steroids had been commonly available before and had been used successfully to treat patients to combat especially bad attacks, but they hadn’t been aggressively used to fight the disease in its early stages. As Dr. Weiner explained, “I applied that idea to using known therapies and not being afraid to use them to shut down a person’s disease.” He believed in attacking the disease with every weapon available, as quickly as possible. For many patients, but not all, it worked.

It worked for me. The numbness began receding—so slowly at first that I wasn’t certain it was real, but as the steroids took hold, the numbness receded all the way back down my leg, where it stopped. Oh my gosh, I thought gratefully, there’s a chance I can have my life back. For the first time I knew that I had a weapon to fight back. Oh, how I hated those steroids—the side effects were devastating—but they meant that, at least temporarily, I could keep the monster at bay. It wasn’t a cure. My leg was still weak and numb, but I could live with that. The numbness was localized, and I could live with that. It was just so hard for me to accept the unrelenting extreme fatigue that had become my new reality. I felt like I was living in a fog, and worse, that I had become a burden.

In This Together

In This Together